Like the European Union or the United Nations today, the League of Nations frequently found itself satirized or criticized for its actions – or the lack thereof – in international politics. The difference being that the League was the first international organization set up to govern as well as maintain peace and collective security globally. How did contemporaries narrate this new actor on the international stage, or frame a League in crisis in the 1930s? This blog post explores these contemporary frames and narratives as a prism to understand representations of the League and perceptions of the international system across borders.

By turning to cartoons, this blog post applies a new cultural lens to uncover contemporary perceptions and feelings regarding the League based on circa 150 British, French, Dutch, and German cartoons.[1] Recently, historians have begun to examine how the League itself perceived and attempted to influence public opinion.[2] However, the media history and perceptions of the League beyond Geneva remain rich yet relatively uncharted territories.[3] This blog analyzes two dominant transnational and national frames: that of a new actor in the 1920s and that of failure in the 1930s. It argues that there are striking cross-border commonalities in how the League was framed as being at odds with the traditional diplomatic system: initially positively as a female embodiment of peace and justice, but later as powerless bureaucrats amidst political crisis. The different national perspectives display the surprisingly gendered and emotional ways in which contemporaries tried to make sense of interwar international relations.[4]

An insightful source

Following the Cultural Turn, historians have discovered cartoons’ value for analyzing contemporary perceptions for a variety of topics, but international organizations remain underexplored.[5] As a source, they can provide insights into contemporary attitudes, values, and emotions towards an issue in ways written sources cannot.[6] This is because cartoons metaphorically frame a political event or complex issue by using metaphors and emotions into a comprehensible narrative to which newspaper readers can relate in one glance. Cartoonists embed their drawings in existing visual and semiotic repertoires, using concepts and narratives which could resonate with readers’ knowledge of politics. Thus, cartoons provide a particularly intriguing angle to uncover how contemporaries made sense of, and, crucially, felt about issues ranging from corruption and elections to gender and international relations.

Strong framing is part and parcel of cartoons. In order to be quickly grasped, cartoons tend to portray issues either very negatively or very positively, with stark contrasts, symbols, and metaphors to exaggerate oppositions.[7] However, in doing so cartoons also engender a biased sample of perceptions and feelings. After all, they tend to lend themselves more for satirical criticism and negative emotions, rather than happiness or praise, and moreover tend to cover issues hotly discussed in politics and society. Nevertheless, because of these strong frames, cartoons do lend themselves for analyzing how cartoonists from different countries sought to contrast a novel, idealist League of Nations with traditional power politics.

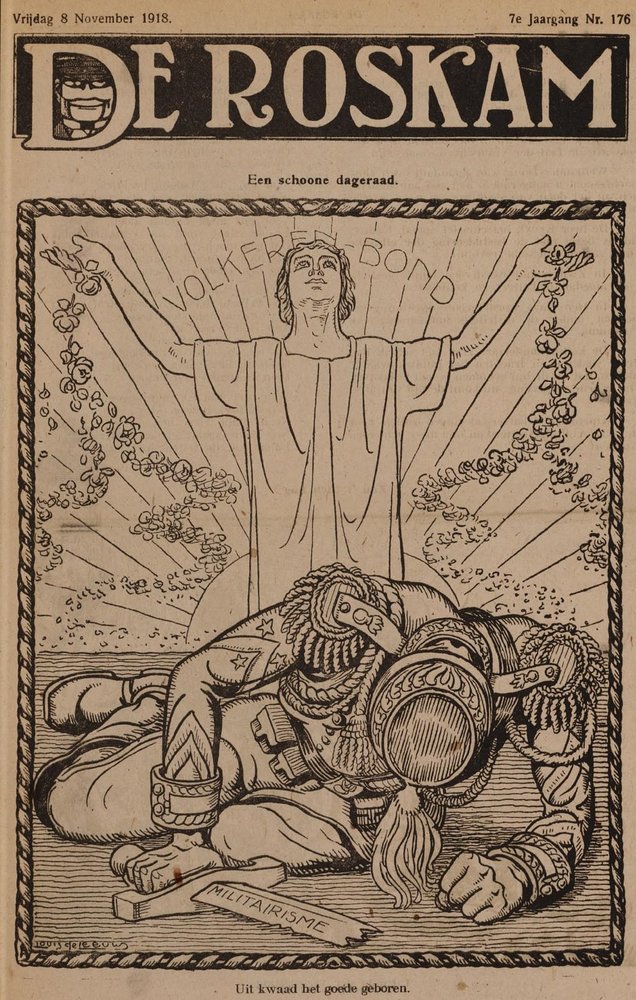

The League as a female fair dawn [Schoone dageraad] over male militarism.

Narratives from the 1920s: a new actress on the international stage

Continuing a 19 th century tradition, most cartoonists tried to fit the League as a novel diplomatic actor into their existing semiotic repertoire of national personifications or allegories to represent international politics.[8] Cartoonists predominantly represented the League as a personification of Lady Justice, as a positive female embodiment of international peace and order.[9] German cartoonists also depicted the League as such, but more frequently opted for the French Marianne to frame the League as an explicitly French and Allied extension of the Versailles Diktat.

The symbolical representation of the League as a female harbinger of peace and justice vis-à-vis cynical diplomats demonstrates how cartoonists perceived it as an idealist force in international politics. Representations of the League as a female judge further underline how the League became enmeshed with idealist conceptions of international law ending war.[10] This becomes especially clear when ‘she’ becomes a focal point of fears of failure and broken promises towards the late 1920s.

Lady League looking back at ten years of unsuccessful world co-operation in disarmament.

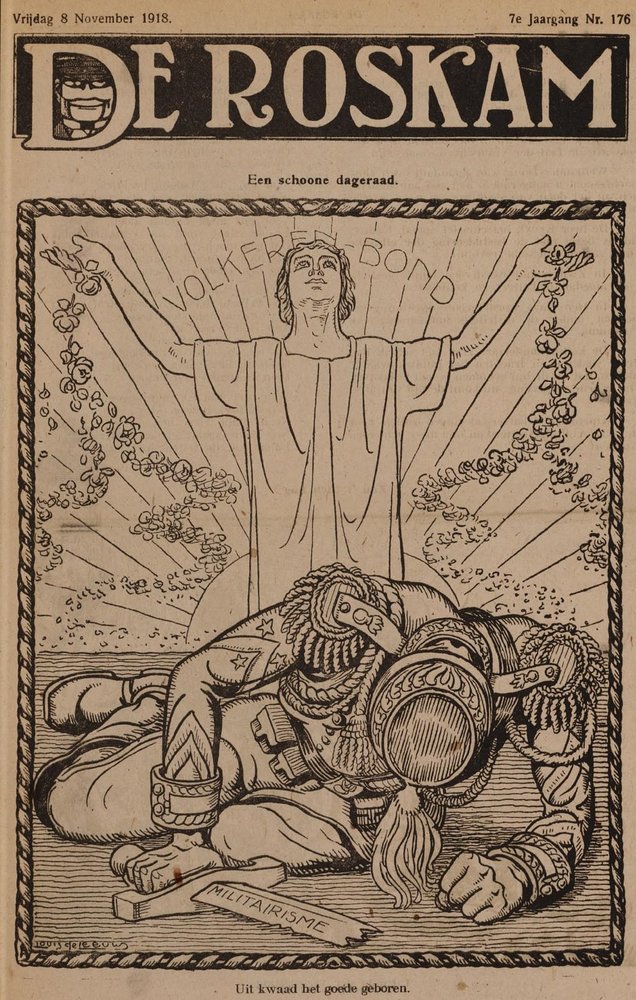

The framing of the League’s female personification gives insight into how the League was perceived as an actor. Three frames or metaphors are recurrent transnationally. Firstly, that of the strong and powerful Lady Justice or Peace who, despite hardships, is depicted as an independent actor working for the common good. The second metaphor is that of the school teacher, judge or disciplining mother. British and French cartoons – but tellingly no German ones – framed the League as an impartial arbiter disciplining unruly boys who represent the revanchist powers of Europe.[11] Conversely, cartoons from after the Sino-Japanese conflict of 1932 portray the League as failing in disciplining them. The third variety frames the League as a weak-willed woman who is dependent on male Great Powers. It depicts a tarnished and weak Lady Justice, at times beleaguered in court, a sick or dead League or, in one extreme case, as a woman about to be violated by Mussolini.[12] However, these cartoons do not blame ‘her’, but rather the male politicians who failed the League.

When cartoonists sought to represent international politics revolving around Geneva, they were more inclined to draw male protagonists rather than an independently acting ‘Lady League’. To be sure, several cartoons also personify the League as a man, although a rather unmanly one. It is a weak man incapable of action, or an overburdened bureaucrat or judge losing control. Tellingly, especially German cartoonists use such male personifications.

(Left) A strong Lady Justice in a social democrat magazine versus Nazi agitators. (Right) Mars informs the League war has already settled the Abyssinian question.

These representations of the League are clearly connected to the wider historical context. It is no coincidence that the League was frequently personified as a woman. Like the League, women were new on the ‘public stage’ in an era of women’s rights, suffrage and an increased female presence in society and politics following the war. Furthermore, the League’s covenant enshrined gender equality and the organization could count on massive support by women’s organizations from all over the world.[13] After the economic crash of 1929 and the political crises following it, the League was increasingly represented as a weak woman or a frail old man, both standing no chance against national, masculine figures. These changed gendered frames are imbued with fascist and authoritarian idealizations of virile manliness and actions versus dozed-off deliberation and pacifist idealism.[14] Cartoons of the League thus became a canvas of all sorts of criticisms of the weak-willed liberal-democratic Versailles order and the lost ideals of the early 1920s.

A League under fire: crisis and failure in the 1930s

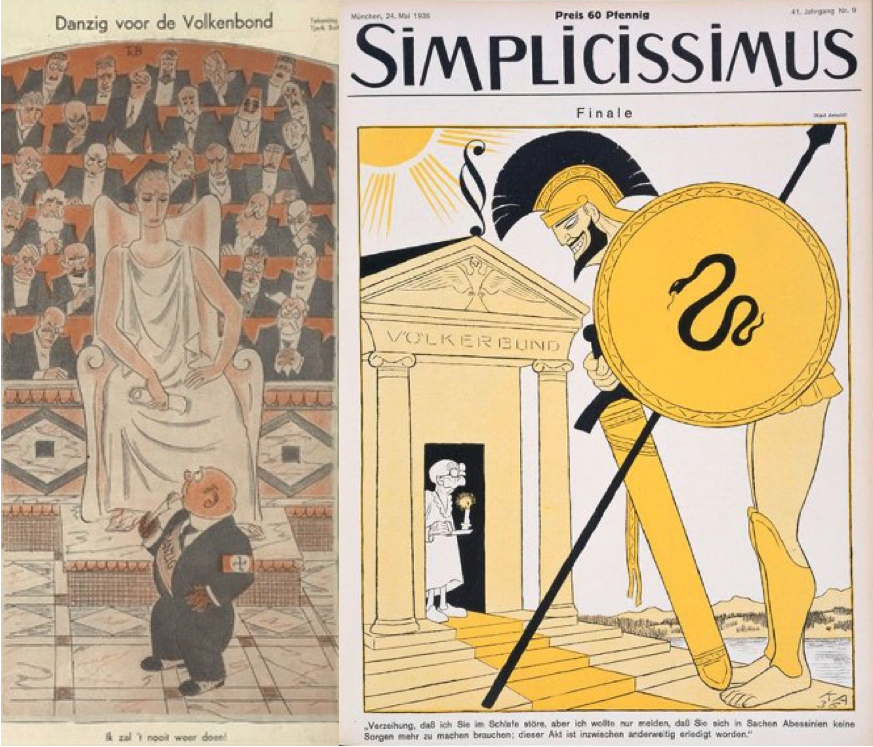

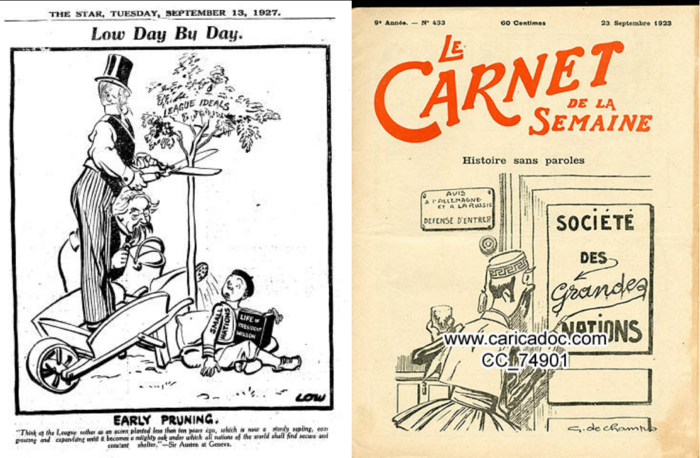

In a wider context of international tensions, it is striking how often the League was not the centerpiece of attention, but rather a stage for others to make politics.[15] In the 1920s, criticism was focused on a League which favored the Great Powers, particularly France and Great Britain. German artists chose French and British caricatures to represent the League, but British and French cartoonists were not blind to the enmeshment of their national interests and those of the League either.[16]

(Left) Chamberlain and Briand say goodbye to the League's ideals while a scared boy of the 'small nations' can only look. (Right) Greece discovers that the League of Nations has become the Society of Great Nations.

After 1930, however, the common depiction of the League in international relations is that of a mere material stage for the Great Powers, foregrounding the League’s impotence. Moreover, the identification of the Geneva system with the Versailles order became a recurrent theme, particularly to cartoonists who criticized those who failed to uphold it. For example, British and Dutch cartoonists draw how Mussolini and Hitler undermine the League, while the Allied powers stand by, passively. In a way, cartoons represent contemporary perceptions of a return to the ‘Old Diplomacy’ of Realpolitik and bilateralism, by-passing Geneva.[17]

The Palais des Nations as a stage for Great Powers, with France and Britain preferring to remain offstage.

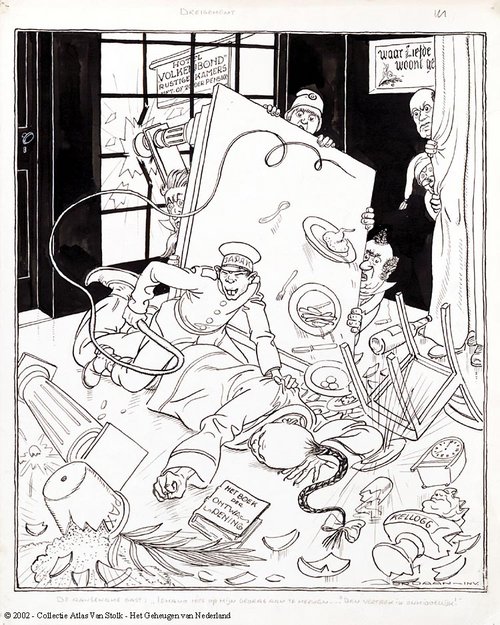

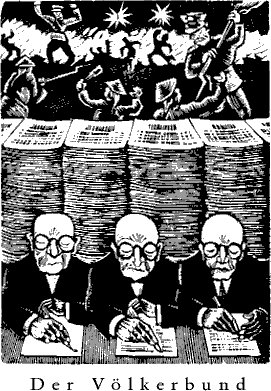

Squabbling diplomats and apathic technocrats

Another common transnational frame represents the League mimetically, as a congregation of white, male diplomats in tailored suits. Ironically, precisely this mode of representation is one of the most scathing cartoon comments on the League’s functioning.[18] A general theme of such ‘realist’ framed depictions is that of a League being ‘all talk and no action’; a group of generic diplomats endlessly discussing disarmament, yet nothing comes of it.[19] It is both a critique of a new, technocratic order and of a return to an old order of selfish national prerogatives which paralyzed the League.

The League as apathetic technocrats in the face of war.

It is salient how criticisms of the League as an ineffective gentleman’s club include both cartoonists working for German national socialist magazines or Dutch and British liberal outlets. Even a liberal and staunch anti-Nazi cartoonist like Erich Schairer negatively portrayed the Geneva organization as aged technocrats who continue their work obnoxiously while war rages in China.[20] It is a multi-faceted critique of the League which appeals to a demand for strong, personal action in a context of indecisive, flaky liberal democracies versus the allure of decisive and manly authoritarianism – a demand visible in Weimar Germany, but also the Netherlands.[21] Beyond these transnational commonalities, there are clear national differences in narratives of a League in crisis during the 1930s.

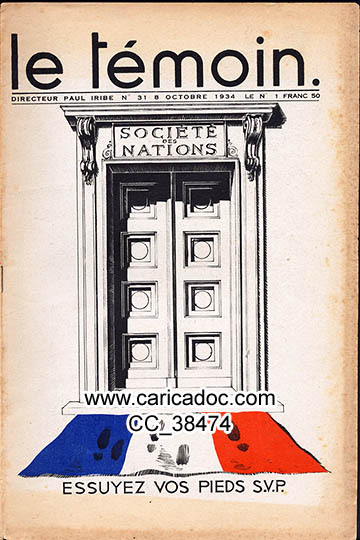

A League in despair: French and German perspectives

In France, the unraveling of the Versailles order caused fears for security.[22] Whereas German cartoons identified Geneva with Marianne, French cartoonists portrayed either a cold and distant League or an organization which begged an isolated France for help. Frequently, caricatures oozed both despair and fear over the fact that France stood alone in upholding the Treaty of Versailles. One cartoon shows a fearful Marianne begging a condescending, dark-clad and indifferent League to impose sanctions, while Britain’s John Bull remains aloof.[23] Sometimes, as below, a simple image speaks a thousand words on how French national pride was insulted and French interests neglected.

France as doormat to the League

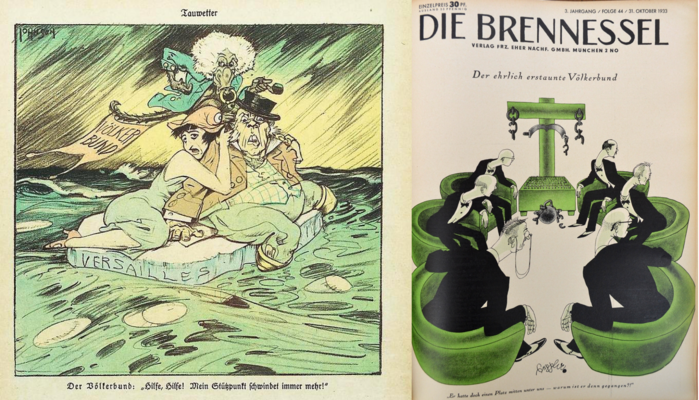

German cartoonists, on the other hand, almost gleefully portrayed a France in despair. One cartoon depicts Marianne glaring at a smug looking German diplomat leaving the Palais des Nations while she mutters “Outrageous, even though I have promised him contractual disarmament for over fourteen years, he still does not want to believe it!” – a cynical jab at France’s extreme reluctance to either disarm or allow Germany rearmament.[24] Recurrently, cartoons highlighted French and English frustration and anxiety over Germany no longer abiding the rules of Versailles.

(Left) The Allied post-war order: a sinking ship. (Right) Germany liberating herself from the League.

The League forms a focal point for pride or joy in Germany regaining equality outside of the Geneva system. One cartoon in the national socialist Die Brennessel nearly mimetically represents the League as condescending diplomats who had chained Germany to a torture chair. Poignantly, they act surprised when their ‘equal’ breaks free from the chains of Versailles. There are clear continuities in how German cartoonists criticized the League and its relation to Allied interests in strongly emotional frames. The openly hostile and at times martial frames in which the liberal Versailles order is taken under fire, however, constitute a new development from the failed World Disarmament Conference of 1932-34 and the shift to Nazi rule onwards.[25]

Small state and idealist perceptions

Dutch and British cartoons evoked rather different emotions. Paradoxically, several Dutch cartoonists criticized the League’s response – or rather, the lack thereof – to crisis by portraying the League as emotionless, represented by apathic diplomats. Although French cartoonists also depict the League as an indifferent diplomat, this specific and recurrent representation of a League machinery apathic to the atrocities and plights of ‘lesser’ powers can be regarded as a specific ‘small state’ perspective on the international system of the 1930s. Furthermore, cartoons of the organization’s precarious position in defending smaller states versus belligerent powers invoke strong emotions. Often, a fearful Lady League sees herself confronted with or humiliated by menacing looking Japanese or Mussolini, usually reinforced with a light-dark contrast.[26]

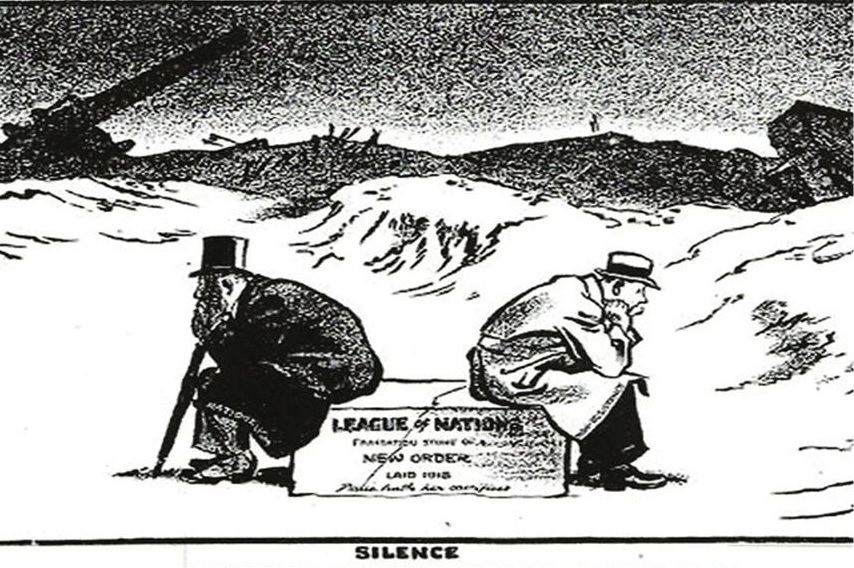

British cartoonists likewise employ the frame of humiliation, but also that of regret to represent the failures of League idealism. Time and again the League was portrayed as a dejected, timid and ill-dressed woman who stands alone, abandoned by politicians.[27] The New Zealand born cartoonist David Low in particular used his cartoons to frame the betrayal or failure of internationalism and idealism.[28] His drawings convey a deep sense of regret by letting politicians visit Lady League’s sickbed or even grave for not having supported her.

Regrets about the failed new order of the League, with the ruins of the Great War in the background.

However, following the League’s failures in the face of Italian, German, and Japanese aggression as well as in coordinating an international response to the economic crisis, Low’s idealist perspective had become an outlier during the 1930s. Whether positively or negatively, the League came to signify the failure of international co-operation in the face of nationalism and revanchism, although often the Great Powers rather than the League itself were blamed. The League’s subsequent shift towards social, economic and technical work was not lauded – on the contrary, cartoonists vehemently criticized the technocratic nature of the organization, and its failure to take, let alone defend, a political stance.[29] These narratives of failure not only had an impact on the international role the League could or still wanted to play in the 1930s, but moreover cast their shadow on its legacy for decades to come.[30]

Concluding remarks

Cartoons provide a prism for studying how contemporaries tried to interpret the League’s role within the interwar international system. The League was invariably depicted as being out of touch with the traditional diplomacy of Great Powers and Realpolitik, either because of its idealism or its apparent failure to deal with these in the 1930s. Intriguingly, cartoonists across countries used a very gendered and emotional semiotic reservoir to represent the League and international politics, which inter alia overlaps and collides with contemporary perceptions of masculine, authoritarian leadership.

This survey of the specific ways in which international organizations are narrated and framed in cartoons hopes to inspire further research into how narratives of IOs are articulated. This particularly pertains to what extent these discursively co-construct the actual space within which international organizations had to pursue policies and legitimize themselves, as well as deal with rival organizations and reluctant member states. How did the articulations of these images and narratives shape the self-perceptions of international organizations, as well as limit and shape what they could do on the international stage?

References

[1] Some 30 cartoons from Punch have also been included in the analysis, but unfortunately cannot be shown here due to exorbitant copyright costs. For a similar approach: Jos Gabriëls, ‘’Cutting the Cake: The Congress of Vienna in British, French and German Political Caricature,’’ European Review of History: Revue européenne d’histoire 24, no. 1 (2017).

[2] Tomoko Akami, ‘’The Limits of Peace Propaganda. The Information Section of the League of Nations and Its Tokyo Office,’’ in International Organizations and the Media in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Exorbitant Expectations, ed. Jonas Brendebach, Martin Herzer, and Heidi Tworek (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2018), 70-90; Stephan Wertheim, ‘’Reading the International Mind: International Public Opinion in Early Twentieth Century Anglo-American Thought,’’ in The Decisionist Imagination: Sovereignty, Social Science and Democracy in the Twentieh Century, ed. Nicolas Guilhot and Daniel Bessner (New York: Berghahn, 2019); Emil Eiby Seidenfaden’s ongoing PhD research on the public legitimization strategies in the League Secretariat at Aarhus University and Pelle van Dijk’s on the League and the emergence of an international public opinion at the European University Institute.

[3] Heidi Tworek, ‘’Peace Through Truth? The Press and Moral Disarmament through the League of Nations,’’ Medien & Zeit 25, no. 4 (2010); Timo Holste, ‘’Tourists at the League of Nations. Conceptions of Internationalism around the Palais des Nations, 1925-1946,’’ New Global Studies

[4] Patrick Finney, ‘’Narratives and Bodies: Culture Beyond the Cultural Turn,’’ The International History Review 40, no. 3 (2018): 621.

[5] See e.g. Marij Leenders and Joris Gijsenbergh, ‘’The Image of Prime Minister Colijn: Public Visualization of Political Leadership in the 1930s,’’ in Repertoires of Representation: New Perspectives on Power from Ancient History to the Present Day, ed. Harm Kaal and Daniëlle Slootjes (In press, 2019); Priska Jones, Europa in der Karikatur. Deutsche und britische Darstellungen im 20. Jahrhundert(Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag, 2009); cf. Patricia Gilmartin and Stanley D. Brunn, ‘’The Representation of Women in Political Cartoons of the 1995 World Conference on Women,’’ Women’s Studies International Forum21, no. 5 (1998).

[6] Frank Palmeri, ‘’The Cartoon: The Image as Critique,’’ in History Beyond the Text. A Student’s Guide to Approaching Alternative Sources, ed. Sarah Barber and Corinne M. Pennist-Bird (London and New York: Routledge, 2009), 92-93; Josh Greenberg, ‘’Framing and Temporality in Political Cartoons: A Critical Analysis of Visual News Discourse,’’ Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie 39, no. 2 (2002): 194-195; Thomas M. Kemnitz, ‘’The Cartoon as Historical Source,’’ The Journal of Interdisciplinary History4, no. 1 (1973): 83-84. Gilmartin and Brunn, ‘’The Representation of Women in Political Cartoons,’’ 535-6.

[7] Larry Bush, ‘’More than Words: Rhetorical Constructs in American Political Cartoons,’’ Studies in American Humor 3, no. 27 (2013): 68-70.

[8] Kemnitz, ‘’The Cartoon as Historical Source,’’ 83-84, also see Chris Williams, ‘’The Shadow in the East,’’ Media History 23, no. 3-4 (2017).

[9] Stephan Wertheim, ‘’The League of Nations: A Retreat from International Law?,’’ Journal of Global History 7 (2012); a Punchcartoon in which the Goddess of Peace appoints ‘’Lady League’’ as her priestess: https://punch.photoshelter.com/image?&_bqG=39&_bqH=eJzLcPNN8spJS8wtd9cNdMpOdjJ2KjX2yUkyrDSwMrQEYgMwBpKe8S7BzrY.qYnppana.Wnafoklmfl5xWpg8XhHPxfbEiA7NNg1KN7TxTYUpCfLKyvTNCgpL8czXS3e0TnEtjg1sSg5AwAR5CPk&GI_ID[accessed 30-10-2018].Also see: Judy Tzu-Chun Wu, ‘’Gendering American Foreign Relations,’’ in Explaining the History of American Foreign Relations, ed., Frank Costigliola and Michael J. Hogan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 271-283.

[10] See e.g. Alfred Zimmern, The League of Nations and the Rule of Law, 1918-1935 (London: Macmillan, 1935).

[11] For legalist conceptions of international order in the interwar period, see: Jean-Michel Guieu, ‘’International Legal Scholars and the Question of a European Institutional Order in the 1920s,’’ Contemporary European History 21, no. 3 (2012); Wertheim, ‘’The League of Nations.’’

[12] In a 1934 cartoon in De Notenkraker, https://hdl.handle.net/10622/F343841C-96F0-4444-92A8-7147E922F40F – unfortunately, the quality is too low to use.

[13] Glenda Sluga, ‘’Women, Feminisms and Twentieth-Century Internationalisms,’’ in Internationalisms. A Twentieth-Century History, ed. Glenda Sluga and Patricia Clavin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 67-75.

[14] George L. Mosse, The Image of Man. The Creation of Modern Masculinity(Oxford University Press: New York-Oxford, 1996), 155-180.

[15] For such ‘’realist’’ perspectives on the League, see e.g. E.H. Carr, The Twenty Years’ Crisis 1919-1939 (London: Macmillan, 1939); F.S. Nortedge, The League of Nations: Its Life and Times, 1920-1946 (Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1986); for a critical reflection on interwar realism, Michael Riemens, ‘’International Academic Cooperation on International Relations in the Interwar Period: the International Studies Conference,’’ Review of International Studies 7, no. 2 (2011).

[16] Zara Steiner, The Lights that Failed: European International History, 1919-1933 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 299.

[17] Mark Mazower, Governing the World. The History of an Idea (London: Penguin Press, 2012), 116-128, 141-142.

[18] Leenders and Gijsenbergh, ‘’Public Visualization of Political Leadership.’’

[20] Kurt Koszyk, "Schairer, Erich (Pseudonym Adam Heller),’’Deutsche Biografie (2005, online version), https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd118606344.html#ndbcontent [accessed 30-10-2018].

[21] Joris Gijsenbergh and Harm Kaal, ‘’Kritiek op de parlementaire democratie in Nederlandse spotprenten,’’ in Erich Salomon & het ideale parlement. Fotograaf in Berlijn en Den Haag, 1928-1940, eds. Andreas Biefang and Marij Leenders (Amsterdam: Boom, 2014).

[22] Mark Mazower, Dark Continent. Europe’s Twentieth Century (London: Penguin Press, 1999), 63-66.

[23] The front cover of L’Espoir Français in 1935,

[24] The iconic cover of Simplicissimus

[25] Mazower, Governing the World, 180-7; Mazower, Dark Continent, 54-56.

[26] Also see – albeit from a traditional diplomatic perspective – Remco van Diepen, Voor Volkenbond en vrede. Nederland en het streven naar een nieuwe wereldorde 1919-1946(Amsterdam: Prometheus, 1999), 193-240.

[27] See e.g. a Punch

cartoon on Athony Eden abandoning a female League of Nations, punch.photoshelter.com/image [accessed 30-10-2018].

[28] Colin Seymour-Ure, ‘’Low, Sir David Alexander Cecil,’’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (version 24 May 2008, online version), https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/34606 [accessed 30-10-2018].

[29] Patricia Clavin, Securing the World Economy. The Reinvention of the League of Nations, 1920-1946 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 124-128, 162-172.

[30] Susan Pedersen, ‘’Back to the League of Nations,’’ The American Historical Review 112, no. 4 (2007).

Images